Executive Summary

Systemic arterial blood pressure is a tightly regulated physiological parameter maintained through a complex interplay of neural, hormonal, and renal mechanisms. The primary objective of this regulation is to ensure adequate and consistent perfusion of vital organs across a range of physiological states, such as changes in posture, physical activity, and stress. Short-term control is primarily mediated by the autonomic nervous system via the baroreceptor reflex, while long-term control is governed by the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) and the kidneys’ management of fluid and electrolyte balance.

Key Data Points

- Baroreceptor Reflex (Short-Term Neural Control): Specialized mechanoreceptors located in the aortic arch and carotid sinuses detect beat-to-beat changes in arterial pressure. They provide rapid, negative feedback to the brainstem, which modulates sympathetic and parasympathetic output to adjust heart rate, cardiac contractility, and peripheral vascular resistance.

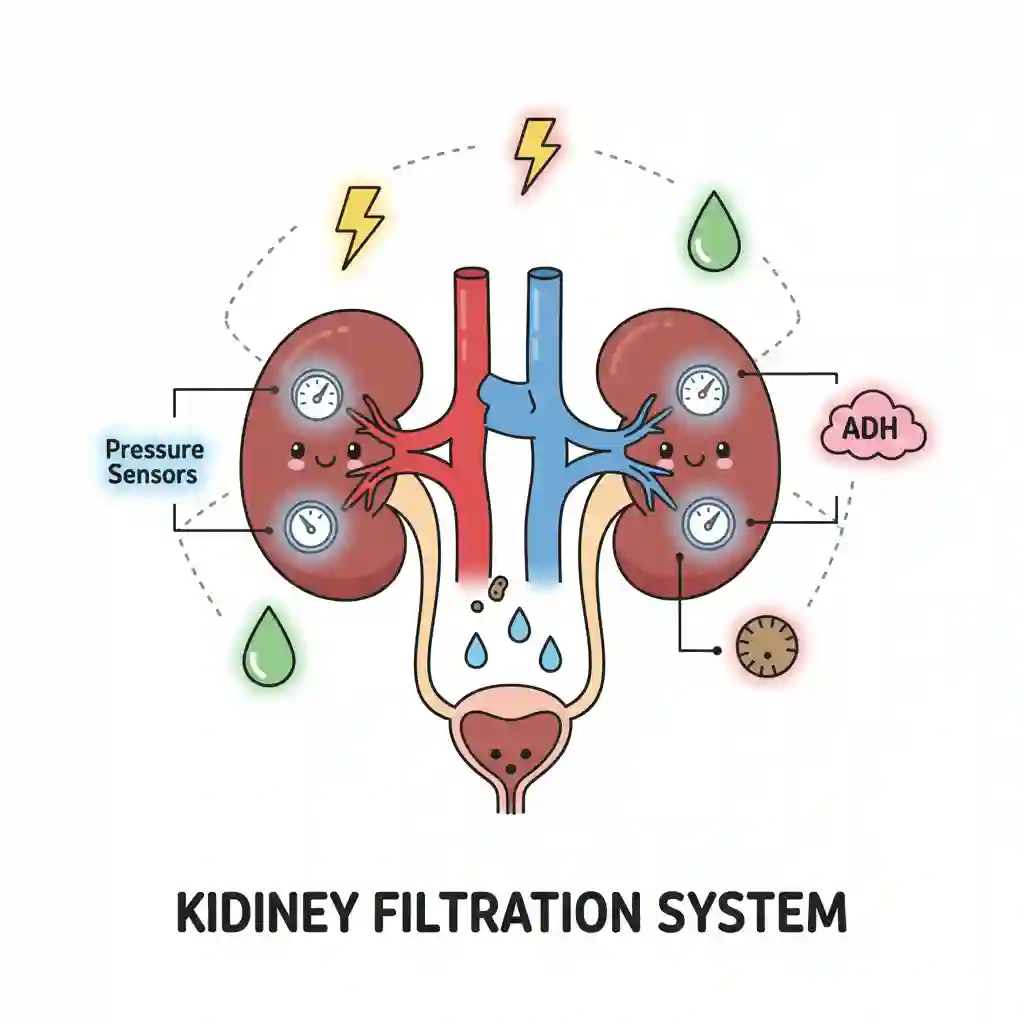

- Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS): A critical hormonal cascade for medium- to long-term regulation. A drop in renal perfusion pressure triggers the release of renin, leading to the production of Angiotensin II—a potent vasoconstrictor. Angiotensin II also stimulates the release of aldosterone, which promotes sodium and water retention by the kidneys, thereby increasing blood volume.

- Renal Pressure Natriuresis (Long-Term Volume Control): The kidneys play a dominant role in long-term blood pressure control by directly linking arterial pressure to renal excretion of sodium and water. An increase in arterial pressure leads to a corresponding increase in sodium and water excretion, which reduces extracellular fluid volume and consequently lowers blood pressure.

- Adrenal Catecholamines: In response to stress, the adrenal medulla releases epinephrine and norepinephrine, which rapidly increase heart rate and cause widespread vasoconstriction, contributing to the “fight-or-flight” pressor response.

Research Methodology / Context

The mechanisms of blood pressure control are a cornerstone of cardiovascular physiology, elucidated through extensive experimental research, including animal models and human studies. Methodologies involve 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) to assess diurnal variations, microneurography to measure sympathetic nerve activity, and plasma assays to quantify levels of renin, angiotensin, and aldosterone. The scientific context is understanding the intricate feedback loops that maintain hemodynamic homeostasis and how their failure contributes to cardiovascular disease.

Clinical Implications

- Pathophysiology of Hypertension: Chronic hypertension is fundamentally a disease of dysregulated blood pressure control. The majority of cases involve abnormalities in one or more of these systems, such as an overactive RAAS, impaired pressure natriuresis, or heightened sympathetic nervous system tone.

- Primary Targets for Pharmacotherapy: The major classes of antihypertensive medications are designed to specifically target these regulatory pathways. Examples include ACE inhibitors and ARBs (targeting the RAAS), beta-blockers (targeting sympathetic neural control), and diuretics (targeting renal volume control).

- Diagnostic Framework for Secondary Hypertension: When investigating secondary causes of hypertension, clinicians assess for pathologies affecting these systems, such as renal artery stenosis (which activates the RAAS) or endocrine tumors that secrete aldosterone or catecholamines.

- Rationale for Lifestyle Modifications: The efficacy of lifestyle interventions is directly linked to these mechanisms. For example, sodium restriction aids the kidneys’ ability to manage fluid volume, while stress management techniques can reduce sympathetic overactivity.